The healthcare industry is in a period of transformation being driven by at least four converging factors: (1) the recognition of serious gaps in the safety and quality of care we provide (and receive), (2) the unsustainable increases in the cost of care as a percent of the national economy, (3) the aging of the population, and (4) the emerging role of healthcare information technology as a potential tool to improve care. These are impacting healthcare organizations as well as individual practitioners in numerous ways that can also be traced to expectations regarding transparency and increasing accountability for results. As depicted in Figure 1–1, the Triple Aim includes the simultaneous goals of better care (outcomes/experience) for individual patients, better health for the population, and lower cost overall. Practitioners and trainees must adapt to a new set of priorities that focus attention on new goals to extend our historic focus on the doctor/patient relationship and autonomous physician decision making. Instead, new imperatives are evidence-based medicine, advancing safety, and reducing unnecessary expense.

The impact of healthcare quality improvement will increasingly influence clinical practice and the delivery of pediatric care in the future. This chapter provides a summary of some of the central elements of healthcare quality improvement and patient safety, and offers resources for the reader to obtain additional information and understanding about these topics.

To understand the external influences driving many of these changes, there are at least six key national organizations central to the transitions occurring

1. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Department of Health and Human Services)—www.cms.govCenter for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) oversees the United States’ federally funded healthcare programs including Medicare, Medicaid, and other related programs. CMS and the Veterans Affairs Divisions together now provide funding for more than one trillion of the total $2.6 trillion the United States spends annually on healthcare expense. CMS is increasingly promoting payment mechanisms that withhold payment for the costs of preventable complications of care and giving incentives to providers for achieving better outcomes for their patients, primarily in its Medicare population. The agency has also enabled and advocated for greater transparency of results and makes available on its website comparative measures of performance for its Medicare population. CMS is also increasingly utilizing its standards under which hospitals and other healthcare provider organizations are licensed to provide care as tools to ensure greater compliance with these regulations. It has adopted a list of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) in 10 categories for which hospitals are no longer reimbursed. This list of HACs includes for 2013: foreign object retained after surgery, air embolism, blood incompatibility, stage III and IV pressure ulcers, falls and trauma, manifestations of poor glycemic control, catheter-associated urinary tract infection, iatrogenic pneumothorax, vascular catheter-associated infection, and surgical site infection or deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism after selected procedures. It is worth noting that CMS is able to generate comparative national data only for its Medicare population because it, unlike Medicaid, is a single federal program with a single financial database. Because the Medicaid program functions as 51 state/federal partnership arrangements, patient experience and costs are captured in 51 separate state-based program databases. This segmentation has limited the development of national measures for pediatric care in both inpatient and ambulatory settings. Similarly, while the reporting of HACs is uniform across the United States for Medicare patients, in the Medicaid population it varies by individual state.

2. National Quality Forum—www.qualityforum.org/Home.aspxNational Quality Forum (NQF) is a private, not-for-profit organization whose members include consumer advocacy groups, healthcare providers, accrediting bodies, employers and other purchasers of care, and research organizations. The NQF’s mission is to promote improvement in the quality of American health care primarily through defining priorities for improvement, approving consensus standards and metrics for performance reporting, and through educational efforts. The NQF, for example, has endorsed a list of 29 “serious reportable events” in health care that include events related to surgical or invasive procedures, products or device failures, patient protection, care management, environmental issues, radiologic events, and potential criminal events. This list and the CMS list of HACs are both being used by insurers to reduce payment to hospitals/providers as well as to require reporting to state agencies for public review. In 2011, NQF released a set of 41 measures for the quality of pediatric care, largely representing outpatient preventive services and management of chronic conditions, and population-based measures applicable to health plans, for example immunization rates and frequency of well-child care.

3. Leapfrog—www.leapfroggroup.orgLeapfrog is a group of large employers who seek to use their purchasing power to influence the healthcare community to achieve big “leaps” in healthcare safety and quality. Leapfrog promotes transparency and issues public reports of how well individual hospitals meet their recommended standards, including computerized physician-order entry, ICU staffing models, and rates of hospital-acquired infections. There is some evidence that meeting these standards is associated with improved hospital quality and/or mortality outcomes.

4. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality—www.ahrq.govAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is one of 12 agencies within the US Department of Health and Human Services. AHRQ’s primary mission has been to support health services research initiatives that seek to improve the quality of health care in the United States. Its activities extend well beyond the support of research and now include the development of measurements of quality and patient safety, reports on disparities in performance, measures of patient safety culture in organizations, and promotion of tools to improve care among others. AHRQ also convenes expert panels to assess national efforts to advance quality and patient safety and to recommend strategies to accelerate progress.

5. Specialty Society BoardsSpecialty Society Boards, for example, American Board of Pediatrics (ABP). The ABP, along with other specialty certification organizations, has responded to the call for greater accountability to consumers by enhancing its maintenance of certification programs (MOC). All trainees, and an increasing proportion of active practitioners, are now subject to the requirements of the MOC program, including participation in quality improvement activities in the diplomate’s clinical practice. The Board’s mission is focused on assuring the public that certificate holders have been trained according to their standards and also meet continuous evaluation requirements in six areas of core competency: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. These are the same competencies as required of residents in training programs as certified by the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education. Providers need not only to be familiar with the principles of quality improvement and patient safety, but also must demonstrate having implemented quality improvement efforts within their practice settings.

6. The Joint Commission—www.jointcommission.orgThe Joint Commission (JC) is a private, nonprofit agency that is licensed to accredit healthcare provider organizations, including hospitals, nursing homes, and other healthcare provider entities in the United States as well as internationally. Its mission is to continuously improve the quality of care through evaluation, education, and enforcement of regulatory standards. Since 2003, JC has annually adopted a set of National Patient Safety Goals designed to help advance the safety of care provided in all healthcare settings. Examples include the use of two patient identifiers to reduce the risk of care being provided to an unintended patient; the use of time-outs and a universal protocol to improve surgical safety and reduce the risk of wrong site procedures; adherence to hand hygiene recommendations to reduce the risk of spreading hospital-acquired infections, to name just a few. These goals often become regulatory standards with time and widespread.

adoption. Failure to meet these standards can result in actions against the licensure of the healthcare provider, or more commonly, requires corrective action plans, measurement to demonstrate improvement, and resurveying depending upon the severity of findings. The JC publishes a monthly journal on quality and safety, available at http://store.jcrinc.com/the-joint-commission-journal-on-quality-and-patient-safety/.

Finally, advances in quality and safety will be impacted by the provisions of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) and Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) enacted by the United States government in the past 2 years. These laws and their implications are only beginning to be understood in the United States. The landmark 2010 federal healthcare legislation will provide for near-universal access to health care, and now that the Supreme Court has upheld the law, states are beginning the process of creating healthcare exchanges or deferring to the federal government to do so. It is likely that changes in payment mechanisms for health care will continue irrespective of ARRA/PPACA, and current and future providers’ practices will be economically, structurally, and functionally impacted by these emerging trends. Furthermore, changes in the funding and structure of the US healthcare system may ultimately also result in changes in other countries. Many countries have single-payer systems for providing health care to their citizens and often are leaders in defining new strategies for healthcare improvement.

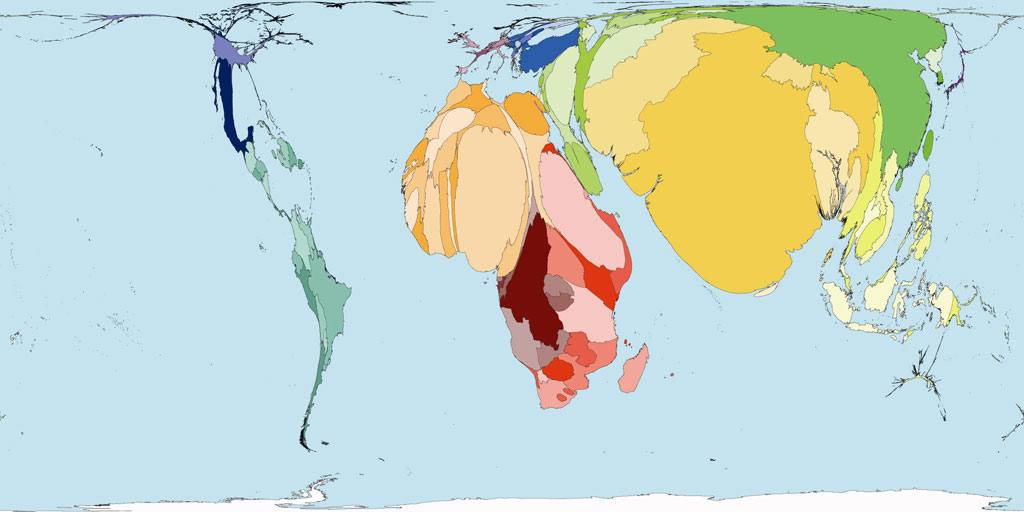

World Neonatal Death

World Neonatal Death